The Privatization of a Community: The Amana Society

Or, when privacy matters more than community

The Amana Colony in the United States evolved from an early 18th-century religious movement called The True Inspirational Congregation. The movement fled persecution in Germany by both the state and the Lutheran Church, and moved to America, first settling near Buffalo, New York. By 1856, the settlers had moved to Eastern Iowa, where, in order to conform to Iowa law, they incorporated as a business named The Amana Society in 1859. The Society established the seven villages that made up the colony. Today, these villages – Amana, East Amana, High Amana, Middle Amana, South Amana, West Amana, and Homestead – are tourist attractions.

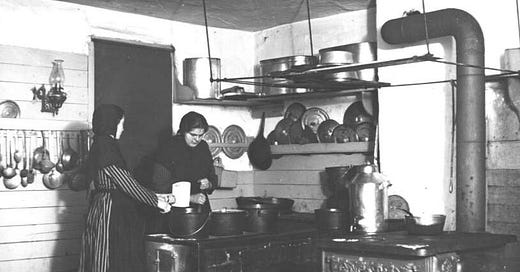

Each village in the Amana Colony was communal and started out self-sufficient. Families lived in suites in houses owned by the community. They ate together in a common dining room, eating food prepared in a common kitchen. The community collectively owned all land, buildings, and means of production. This included houses, livestock, equipment, and other resources. Residents owned only personal items and clothing.

The villagers made their own products using skills passed down through generations. They grew their own food. Governance was administered by a council of elders. Eventually, the community bought machinery and supplies from external sources, which helped them sell their crops and manufactured products to others outside the community. Over time, selling to outside sources became a significant source of revenue for the community.

It all came to an end on May 2, 1932, when the community went private. The event has come to be known as The Great Change.

The Great Change

There were many reasons for the Great Change. Probably the most profound was the economic stress caused by the Great Depression. The community couldn’t sell its crops to buyers outside the community. Agricultural markets had collapsed. The woolen and flour mills that had provided manufacturing income caught fire in the 1920s. The community was reduced to subsistence farming.

There were also cultural tensions. The Amana Society was a religious organization that adhered to Radical Pietism, an attempt to practice ‘true” Christianity and not the “false” versions of institutional churches. There were many rules governing how members lived their lives. Members were expected to work long hours for a meager allowance. Also, members needed the Elders’ permission to marry, but once permission was granted, the betrothed had to wait two years for the marriage to take place. Another restriction was that members could not sell items to outsiders for money and keep the cash for personal use.

And then there were the church services. Members were expected to attend 11 church services each week: there were the nightly evening prayers (Nachtgebet), plus additional services on Wednesday, Saturday, and twice on Sunday.

In short, the Amana Community was not a 1960s commune where members shared assets in common while leading a libertine lifestyle. Everything about living in the Amana Community was hard, from the grueling work requirements to the relentless spiritual rituals. Early on, the hardness of it all was an inspirational feature, an expression of the membership’s commitment to their faith. By the twentieth century, it became, for many, an annoying bug.

Divvying up the Goods

The privatization of the Amana Community was a formal business undertaking. The community was divided into two corporations: The Amana Church Society and the Amana Society. The Amana Church Society was concerned with religious and social welfare matters. The Amana Society dealt with commercial affairs. Labor without in-kind compensation was abandoned, and each working member earned a wage. Wealth was represented by shares of stock, which were of two kinds. Each member was granted a single share of voting stock. But a member also received non-voting stock, the number of shares determined by years of service within the community.

The Great Change transformed community members into owners of private property. At the material level, members owned their homes, livestock, and vehicles. The land of the various villages was owned by the Amana Society Corporation, in which members held stock, but the real estate conveyed to members was residential and, in most cases, sold to its occupants. Private farming was conducted by members leasing land from the corporation for their private use. Members were now obligated to pay property taxes. Farmland retained by the Amana Society, Inc. was taxed as corporate property, while leased plots were subject to individual tax obligations based on use and value. Since the community was not a formal municipal entity, property taxes were paid to Iowa County. (Iowa is the name of the county in the State of Iowa where the villages are located.) Members were also now responsible for paying income taxes and sales taxes. (State income and sales taxes were introduced in Iowa in 1934.)

Overall, the Amana Community was transformed from a communal organization to one based on private property, money-making, and profit. As such, wage-earning in an economy based on commercial enterprise became a central feature of the Amana experience.

The commercial undertakings of the Amana Society became significant. Community members still farmed, provided professional services, and made crafts, but the scale of production increased to industrial manufacturing. The Amana Woolen Mill, which was started in 1859, became a commercial enterprise under the ownership of the Amana Society as part of the Great Change.

The Woolen Mill was a significant manufacturing facility shipping products domestically until the 1980s, when, due to the pressures of overseas manufacturing, production was cut back, and the company became a boutique manufacturer.

Another major Amana industry was refrigeration. In 1934, George Foerstener, a community member who grew up during communal times, established the Electrical Equipment Co. two years after the Great Change. The company produced walk-in refrigerators. In later years, the firm expanded its manufacturing activities into the consumer market, making refrigerators, upright home freezers, stoves, ranges, and air conditioners. The Radarange, which was the first microwave oven marketed to consumers, was an Amana product.

The Amana Society purchased the Electrical Equipment Co. from Foerstener in 1936, with Foerstener remaining as head of the company for 48 years. The company became a major employer in Eastern Iowa. Over the years, the company has become organized into appliance and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) divisions. Ownership of those divisions would pass among a variety of corporations. Today, Whirlpool Corporation owns the Amana brand, and Daikin Industries, Ltd. owns Amana’s HVAC products.

The private life

The Amana villages prospered materially under private ownership. Under the communal system, members had little or no choice about where they lived, the clothes they wore, how they worked, and even the food they ate. Whereas previously they had little choice in the matters that affected their lives, after privatization, they suddenly had many.

One of the first consequences of the Great Change was that meals were no longer prepared in a communal kitchen or served in a common dining room. As a result, members’ eating habits changed. During communal times, rather than serving meat in individual portions, it was easier and more efficient for the cooks to add it to stews prepared in large pots that could serve many. The Great Change introduced kitchens that were private to the family. Privatization made it possible for people to eat any food they could raise or buy. One woman reported that, at last, she could have a steak with her meal.

The Great Change also brought about higher levels of education. In the communal era, formal schooling stopped at age fourteen. After the Great Change, high schools were established, and many teenagers went on to college. The introduction of high schools required the community to hire teachers from outside the community to staff them. As a result, the villages became more open to external influences. As members became more aware of the world outside the community, younger adults left to join that world. The community maintained its spiritual roots, but materialism and commerce also became part of the social fabric.

Today, under two thousand people live in the seven Amana villages. The Amana Church continues to have a significant presence in the community. There are still Elders overseeing the Amana Church Society. The communal experience is no longer a way of life but rather a commercial theme that is emulated by the retail businesses operating there. For example, The Ronneburg Restaurant and the Ox Yoke Inn feature communal dining, but sadly, given that the diners do not work in the kitchen, the practice is more of a symbolic tourist attraction than a genuine experience in communal sharing.

The public vs the private

The idea of shared public space is nothing new in the United States. Farmers grazed their cows, and militias trained for battle on Boston Common in the Massachusetts Bay Colony as far back as 1634 when William Blaxton sold the 44 acres of land to Governor John Winthrop for £30 ($5,455 adjusted). Winthrop raised the money from a one-time tax and turned land over to the colony for common use.

New York’s Central Park – 60 city blocks long, smack dab in the middle of one of the most expensive pieces of real estate in the world, the island of Manhattan – was and is shared space available to all, not just the wealthy who line 5th Avenue and Central Park West. Unlike the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris, which were the private playground of Queen Marie de' Medici and then made public as heads rolled during the French Revolution, Central Park has always been a public space. You don’t need proof of membership to get in. It’s open to all. However, these lands are public, not communal, intended only for limited use, which in modern times is recreational. The communal nature of the seven villages that make up the Amana community was foundational to a way of life until the Great Change. No one person owned a piece of property; all members owned all the property. All depended on the common space and a common purpose to survive.

And yet, it didn’t last. It turned out that people in the villages wanted privacy, choice, and money more than a communal experience.

Today, we live in an increasingly privatized world. Placing value on the common space and the common good might very well be things of the past. When a community abandons the common good and focuses on individual well-being, social cohesion degrades, and trust in others erodes. There is no implicit social contract. Privacy affects who we see as potential fellows and helpers. Those outside the private space are potential encroachers, not compatriots. The dynamic is zero-sum.

In a privatized world, the scope of one’s community is proportional to one’s ability to pay to be in that community. You take care of your place, and I’ll take care of mine. Today, the notion of our place is a fading reality.

But there is a morsel of hope.

Elizabeth Trumpold Momany, Ph.D., is a senior research scientist at the University of Iowa and MIT, as well as a resident who returned to Homestead, one of the Amana villages. She is an elder in the Amana Church Society, a member of the Historic Preservation Commission, and is featured in the 2024 PBS documentary, Amana: A Story of Community, Faith, & Resilience. She says the following.

“One of the things that I think was a clear remnant of communal Amana is that we were raised with the understanding that everybody had to help everybody else, and they had to do for their community…You're here for a whole group of people, and that you have a responsibility to all the people around you to make things better and to do it better…[People] look out for you if they notice there's a problem, they try to help you however they can. I think that's important; now we're trying to preserve that and that's become far more difficult.”

As Momany says, it is difficult. The hope is that it remains possible.