The Price of Paperless

Or, when anything prints

I've written a number of books about computer programming. When I first started writing them, my publishers required that I adhere to a very strict submission process that involved creating an outline of the entire content of the book, down to the third level. Each first-level entry was a chapter in the book and had to include an estimated page count for that chapter. The figure below is an example of such an outline.

The page count was important because it enabled the publisher to estimate how much paper to buy in order to print the book.

When it came time to write the book, I had to stay as close to my page count estimates as possible because if I didn’t, the cost of the paper for the book would go up, and the per-unit profit of each book would go down.

Page count was serious business. I know of situations in which entire chapters of a programming book were cut because the page count was too high. A publisher’s ability to make a profit depended on being able to control page count and also to distinguish between essential and superfluous content. Publishers were willing to absorb the cost of the paper that went with printing essential content. Superfluous content was a “nice to have”.

But that was then, and this is now.

An Avalanche of Content

Today, when it comes to the web, there is no paper cost involved with publishing, just as there is no film cost involved with photography or movie-making. In the past, content creators gave a certain amount of forethought to the things they made due to the cost of materials. Today, it’s a cost-free environment. Anybody with a smartphone can write a blog, take a photo, or make a movie. And, they do.

Given the explosion of online publishing sites such as the one I am using now, not only can anybody be a content creator, they can be a publisher, too, albeit a publisher without the constraints or obligation to support the quality assurance services that commercial publishers provided in the past.

My first programming book had four editors: an acquisition editor, a technical editor, a copy editor, and a graphic editor. My last piece published on a tech website had one editor. I was fortunate to have that. There are sites out there that rely on reader’s comments as their quality assurance mechanism, which, as strange as it seems, can be a double benefit. You get free quality assurance services along with increased reader engagement. (High reader engagement is a key factor in a publication’s success. But this is another story for another time.)

The result of a publishing model with diminishing production costs is that we’re subjected to an avalanche of content. Combine the avalanche of content with the game-changing dynamic of going from an income model based on advertiser revenue to one based on subscription fees paid by random readers, and you get a publishing landscape that is competitively brutal, questionably reliable, and concerned primarily about one thing: subscribers.

When Kitsch Counts

Presently, subscriptions provide the largest portion of revenue for the New York Times. They’re nearly twice that of advertising income. Twenty years ago, most revenue came from advertising.

Whereas advertisers buy according to the circulation of the newspaper, subscribers buy according to interest. Newspapers at the level of the New York Times need millions of subscribers to stay in business. The way to get as many subscribers as possible is to cast a wide net for readers and hope a portion of those readers subscribe. This means publishing not only news but also other content as well. Relegating that “other content” to the back pages of the publication won’t do. To get the bucks, non-news content needs to be front and center, too.

Take a look at the graphic below. It’s the front page of the New York Times from April 12, 1970. The above-the-fold stories are about topics that are pretty important: presidential actions and astronauts going to the moon. In the scheme of things, this is newsworthy material.

Now, take a look at the following image. It’s a screenshot of the top of the New York Times home page on November 30, 2024. Look at the stories deemed important enough to be shown at first viewing: Rebels Control Most of Syria’s Largest City and How Do New Streets Get Their Name?

Of course, the situation in Syria is news that is indeed worth reporting. Matters of the sovereignty of the nation-state are important. But a story about street naming is about as trivial as you can get. Nonetheless, in the realm of modern newspaper publishing, trivial counts, too.

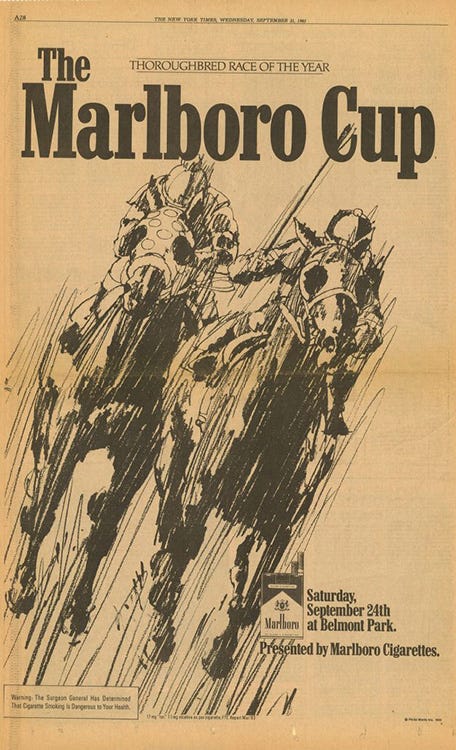

Granted, trivialities have been part of newspaper publishing for a long time. The New York Times was filled with full-page ads promoting everything from cigarettes to liquor.

Putting a full-page ad in the New York Times costs a lot of money, on the order of $150,000 for a single print. Yes, the Times benefits from the ad as revenue, but the intended beneficiary of those ads is the advertiser. The Times is not publishing the ad content to help the reader out. It’s publishing the ad to satisfy the advertiser.

Now, things have changed. The New York Times and other mainstream newspapers might be publishing trivia for the benefit of the reader, but there’s also a good case to be made that it's publishing such kitsch-as-content for its own benefit, too: to get eyeballs.

Getting eyeballs has always been part of the game for as long as newspapers have rolled off printing presses. What’s different this time is that getting eyeballs is the game.

Back when publishers needed to buy paper in order to print their content, newspapers paid a significant monetary price for publishing trivia. The editors gave a long, hard look as to what was going to take up column inches. There was only so much space to go around. Now that the cost of paper is gone, anything can be printed at no additional expense, even trivia. When news and trivia are given equal footing, distinguishing kitsch from consequential content becomes much harder. In other words, when everything looks important, how can something be unimportant? Syria? Street signs? It’s all the same. Right?

Wrong.

The danger of having a population that knows more about how street signs are named than the consequences of political stability in Syria is a real risk, no doubt. But, the greater risk is that, between the two, knowing how street signs are named might be more important.