I just cloned my voice for 5 bucks using a service from ElevenLabs.io. The five-dollar-a-month subscription fee enables me to use the website to record a thirty-second sample of my voice from which the general clone is created. Then, I write up some text and have the clone read and record it to an audio file that I download.

The cloning is surprisingly good. Here is a sample recording of my actual voice reading the first paragraph of Saul Bellow’s book, Ravelstein.

Here is a recording of the exact text used in the recording above; only this time, I used my clone voice.

There are some differences between my voice and the cloned voice, but for those who have never heard my voice in person, the cloned version is pretty convincing. It’s also pretty scary.

My voice is one of the most significant indicators of authenticity I or anybody has. Think about it. How many times have you answered a phone call from someone, heard nothing more than “It’s me.” and know exactly who it was? (Of course, this was in the days before caller ID became commonplace in telephone displays.)

In many ways, I am my voice.

As voice cloning follows other trends in technology and becomes better and cheaper, being able to authenticate someone solely by the sound of their voice becomes a relic of the past. That “hello, it’s me” can just as easily be an AI-generated clone as it could be coming from the vocal cords of a human.

This is a big deal, a very big deal. In addition to the Pandora’s Box of issues it opens in terms of identity replication in film, radio, television, and streaming media, voice cloning goes to the very nature of how we understand reality and truth.

Allow me to elaborate.

Shadows on the wall of a cave

In Book VII of Plato’s Republic, the philosopher Socrates is engaged in a conversation about the Allegory of the Cave. In the allegory, a prisoner is chained to a wall in a cave and can only observe the activities of others by the sounds they emit and the shadows they cast upon the cave’s other walls. The prisoner cannot observe things directly. He can only infer reality from the shadows he sees and the sounds he hears.

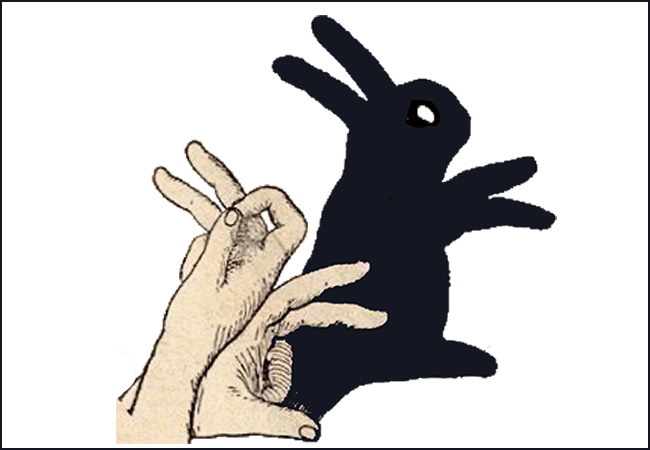

Socrates uses the allegory to explain the indirect nature of learning and knowing, that most of what we take as knowledge is not gathered from direct experience or pure logical thought but rather from stories told to us by others. That telling takes place via word of mouth, the printed word, and, in modern times, audio recordings, motion pictures, and streaming media. It’s like a finger puppet: a shadow of a rabbit is projected onto a wall, but the reality is that the rabbit is nothing more than somebody’s fingers arranged in front of a lightbulb to create the image of a rabbit. The image is one thing; the reality is something else, maybe knowable, maybe not.

A good deal of what we know about the world is based on stories rather than direct experience. Yes, we know that it hurts to put your hand into the flame of a burning candle. And going out in freezing temperatures is uncomfortable. Yet, few of us go outside first to determine if we need a coat. We read the temperature on a cell phone or, in the old days, from a thermometer. We depend on the story the device tells us.

Some of the stories told to us we accept as fact, others as fiction. We distinguish fact from fiction by authentication and trust.

Knowing someone

One way trust is granted is by simply knowing someone. It’s that “knowing someone” that is at risk.

How we know someone matters, particularly when that someone is not in close proximity. Today, with voice and image cloning, that ability to know that someone whom we believe to be a source of knowledge and trust is really “someone” at all is compromised.

Those voices and images that we rely upon for factual information might be nothing more than digital forgeries created by an unknown entity – corporate, government, or a bored teenager in a basement somewhere in East Elbonia. These entities might intend, at best, to do some prankish mischief and, at worst, to influence large segments of the population to ends that are unknown to those being acted upon. Might the intention be some sort of conspiracy that involves a grand plan for world domination? Maybe. Or maybe it’s about something else, something as mundane as to promote sales, whether it’s to buy a car, an air-fryer, or a presidential candidate.

Cloning Oprah's voice to tell you to vote a certain way or buy a certain thing is a no-go. There are too many lawsuits to be had. But what if the voice appears to be that of your neighbor a few doors down? In such a case, will you really be able to tell the clone from the real thing?

A Culture of Inauthenticity

This is the risk we run as voice cloning and technologies like it become better and cheaper. It might very well be the end of authenticity. Maybe it won’t matter that the things we encounter in life will be nothing more than a cloning of something of which we have little or no real knowledge, things that are very much like Plato’s shadows on the wall of a cave. Maybe the only thing that will matter is how these things appear to be.