No Dinner with Stephen Colbert

Or, the nature of a parasocial relationship

The Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) announced recently that it will be canceling The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, effective May 2026. Some believe that the cancellation was due to CBS’s owner, Paramount, attempting to appease the current government of the United States, with the hope of securing the necessary permissions from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) for Skydance Media to acquire the company and bestow a huge windfall on Paramount’s CEO. Others, such as Scott Galloway, think it’s because the show has too much overhead and was losing $40 million a year.

I don't know the actual reason behind the cancellation. It's all a bit murky. But what I do know is that Stephen Colbert’s salary at The Late Show is around $15 million a year, and despite the attention I’ve given him, not once did he call me up and offer to take me out to dinner. With a paycheck of over $288,000 a week, it would be no sweat off his back to treat me to a nice iced tray of a half dozen oysters at Balthazar. But, sadly, no dice.

Why? Because he has no idea who I am. On the other hand, I, along with millions of others, have some idea who he is; at least we’d recognize him and might greet him by name should he pass by on a New York City street. He might return the greeting. He might not. It's a one-way interaction that's not worthy of a dinner invitation. Such is the nature of a parasocial relationship.

The rise of fandom

A parasocial relationship is one in which a person has a deep awareness of and an ongoing affinity with another person, such that the target of that awareness is completely unaware of the person giving the attention. World history abounds with examples of parasocial relationships. They are nothing new.

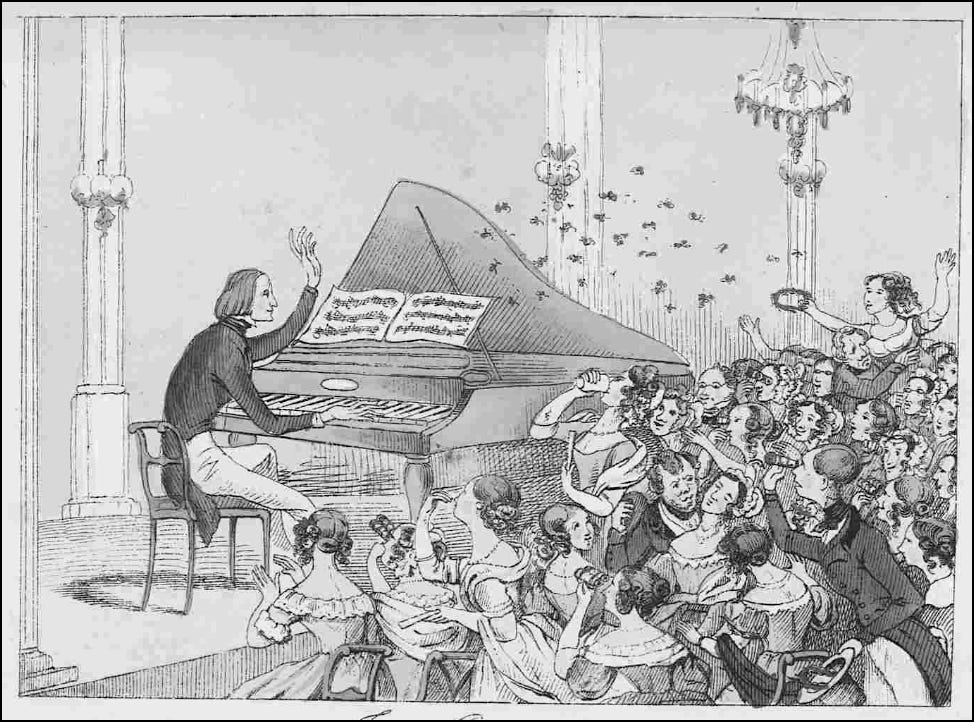

Parasocial relationships emerged as soon as a few performers and leaders could capture the attention of many in recurring, large-scale mass gatherings, thereby becoming famous in the process. In classical Greece, accomplished actors enjoyed fame and prestige; we even know some of their names. In 19th-century Europe, composer and pianist Franz Liszt was wildly famous, playing concerts to packed audiences. His adoration was widespread to the point of fanaticism. Women in the audience, unknown to him, threw their underwear at him as he played. He was a superstar. And yet, he knew few of his followers.

Parasocial relationships became even more widespread with the rise of mass media, advertising, and publicity driven by professional public relations firms. They exploded in the mid-twentieth century as mass media took hold. Figures such as Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Clark Gable, Mae West, Jean Harlow, Bette Davis, and Humphrey Bogart became celebrities in the modern sense: people celebrated for their accomplishments, certainly, but each with a unique image, their brand, which publicists and reporters kept in the public eye. Their mass-produced, autographed photos hung on the bedroom walls of ordinary people hoping one day to meet them, or to gain some of their qualities by osmosis. The public knew their every move, their ups, and their downs. The marriage of baseball player Joe DiMaggio to Hollywood star Marilyn Monroe in January of 1954 made it to the front page of the New York Times. The paper reported their divorce 10 months later. It was all newsworthy and attention-getting. Each morsel of their private lives became fodder for public consumption. The daily “news” about their activities created millions of one-way, parasocial relationships.

Fan clubs, formal organizations devoted to following the life and work of a celebrity, became commonplace. In fact, a sign of status for a fan club was to have the celebrity to whom the club was devoted actually attend a meeting with his or her fans. Whether or not a relationship with the celebrity ever actually continued beyond the meet and greet is a matter for research. Still, in most situations, the fan is an abstraction unknown to the celebrity. And yet, in that abstraction is some sort of affinity. How often have we heard a celebrity say, “I owe it to my fans,” or in more modern terms, “I owe it to my followers”? But that affinity, from celebrity to fan, is limited to momentary episodes of awareness, if any. In the scheme of things, it’s the fan, follower, or sycophant who bears the labor of giving attention. All the celebrity needs to do is perform in some attention-getting manner.

But, back to Stephen Colbert.

A meager cause célèbre

Colbert’s cancellation is a cause célèbre. A cause célèbre is a famous or well-known issue, event, or legal case that attracts widespread public attention and controversy. It often involves sensational, unusual, or highly debated claims of injustice that spark intense public interest and debate. History is filled with causes célèbres, but the phrase entered English as the name of the phenomenon when the Dreyfus Affair in France captured international attention at the end of the nineteenth century. Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish French army officer, was accused and convicted of passing military secrets to the Germans. The veracity of the accusation was doubtful and attributed by many to feelings of anti-Semitism among the French officer corps. The affair became a cause célèbre reported continuously in newspapers around the world. It became a topic of hot conversation among French society. Eventually, Dreyfus was exonerated, despite having spent four and a half years in the savage jungles of Devil’s Island, the penal colony off the coast of French Guiana in South America.

Then there was the case of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg. Julius Rosenberg was a civilian electrical engineer for the U.S. Army Signal Corps. Ethel Rosenberg, his wife, was a homemaker turned union activist. They were convicted of selling secrets to the Soviet Union. They were executed by electric chair in 1953. There was a good deal of controversy about their activities and their subsequent execution. Key to the nature of their cause célèbre was that the Rosenbergs would be the only civilians to date to be executed by the United States for espionage. The trial and conviction were a source of national debate throughout the early 1950s.

Finally, one of the most prominent causes célèbres of the twentieth century was the imprisonment of Nelson Mandela. Nelson Mandela, leader of the anti-apartheid movement in South Africa, was arrested in 1962 primarily for two specific actions: organizing an illegal strike and leaving South Africa without valid travel documents. He spent 27 years in prison before being released in 1990. He went on to become President of South Africa in 1994 after apartheid ended.

The long and the short of it is that history is filled with causes célèbres. And for the most part, they were parasocial relationships. The person at the center of the controversy knew few of those interested in their plight. Occasionally, a prominent figure might step forward, as did the writer Émile Zola during the Dreyfus affair, and as modern-day actors Robert De Niro and Eddie Murphy protested Mandela’s imprisonment. Yet, overall, the relationship was one-way. Anonymous support is not a bad thing in the case of Dreyfus, the Rosenbergs, or Mandela. Those causes célèbres fostered significant change in the way the world works.

The victims at the centers of these causes célèbres suffered to bring about those changes. For eighteen years, Mandela pounded rocks in a limestone quarry on Robbins Island. The Rosenbergs were sent to the Great Beyond. By comparison, Colbert’s suffering is meager. He loses his spot on late-night TV, and for that, he gets to leave CBS with a net worth of $75-$76 million.

Colbert’s jokes on late-night TV didn’t free a nation from the shackles of apartheid or the injustice of anti-semitism. His contribution? A few minutes of political humor delivered nightly, the result of which is one more episode of a media celebrity whose preaching to the choir has little or no impact on the voting behavior of the nation. When you compare Colbert’s current problems to those controversies in the past, to riff on Humphrey Bogart’s line in the movie Casablanca, “It doesn't take much to see that the problems of some late-night media celebrity don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world."

Who’s gonna take me to the airport?

So, what’s my point? It’s this: It seems that we are spending more and more time giving attention to media figures who have no idea who we are at a personal level, and we get little concrete value in return. They get more from us than we get from them. We’re just viewers, fans, followers. We might exist in their world as an email address, a link to a Facebook page, or at the least, a photo in some sort of follower-management software. That’s about as good as it gets. We’re just one of millions. We’re an audience to a Grand Amusement that’s creating a growing number of all too dysfunctional parasocial relationships. Our politics has become cult-like, driven by parasocial relationships on steroids. We adore public figures who know us not.

Now, don’t get me wrong – fans, fandom, and fan adoration have been around for a long, long time, as have the parasocial nature of those relationships. Joe DiMaggio had no idea who was sitting in the last row of the bleachers, cheering him on at Yankee Stadium. To Jerry Garcia, his audience were Deadheads, with just a few of whom he might have had a two-way relationship. The rest were just faces in the crowd.

Celebrities play to the crowd, garnering their attention and, in turn, make millions, whether on purpose or by accident. That’s just the way it is. But to think they are just like you and me, that they’re the type of people we could have a beer with, is delusional. They're not. Take a look at the list below of TV personalities and their yearly salaries.

Stephen Colbert: $15 million

Jimmy Kimmel $: 15 million

Seth Meyers: $5 million

Jimmy Fallon: $16 million

Tucker Carlson: Between $12–$45 million

Bill O'Reilly: $25 million (Fox peak)

Megyn Kelly: $15–$20 million

Lawrence O'Donnell: $4–$7 million (recent range)

Rachel Maddow: $25 million

Anderson Cooper: $20 million

Sean Hannity: $25 million (Fox)

Jesse Watters: $5 million

They are not average Americans. They don’t have to worry about paying for the expenses of everyday life, everything from health insurance, getting the kids braces, to making the monthly mortgage payment. They live in big houses, possibly many big houses. They drive expensive cars. Their refrigerators are always full. Some, such as Sean Hannity, own a private jet. They might have been working class at some point earlier in life, but today they live the lives of the rich and famous. God bless them for their ambition, labor, and good fortune. I begrudge them none of it.

But I am under no illusion that they are just like me. While they might care about me in the abstract, were I to need even the most trivial help, such as a ride to the airport or someone to take care of the dog for a weekend, these TV commentators aren’t people I could contact, let alone rely upon. In fact, I wonder what I could rely upon them for, other than being on time for a regularly scheduled broadcast.

And yet, we give these media celebrities oodles of attention, which they convert into millions of dollars for their employers and themselves. So, whether Stephen Colbert continues on with his antics or gets removed from the media landscape under the taint of political censorship, it matters not to me. All he ever added to my life was some humorous outrage during the two or three times I’ve tuned in.

When it comes to getting help with things that really matter in my life, that help has come from my friends and family, as well as the local police, firefighters, and other public employees and business people in my neighborhood. The clerk at the DMV office, half a mile away, has done more to help me keep my car on the road than Dwayne Johnson (The Rock) ever has.

As for the likes of Maddow, Colbert, Kimmel, and Tucker Carlson, they’re just images on a screen trying to harvest my attention. I care for them no more than they care for me, unless, of course, one of them invites me out to a nice dinner at a fancy restaurant. Then, at least, we’ll both become something more than abstract parties in a parasocial relationship. Who knows? We might even get to know each other well enough to fight over paying the check.