Disclaimer: I am a current member of Kaiser Permanente and have been for twenty years.

Henry Kaiser was an industrialist. He was part of a group of men who ran the companies that changed the physical and commercial landscape of America. They made big things in big ways: steel, railroads, automobiles, steamships, highways, bridges, dams, communication systems, and the armaments of war that allowed the United States to prevail in conflicts during the 20th century. Also, Kaiser, the industrialist, was responsible in good part for bringing health maintenance organizations (HMOs) into the mainstream.

Not a nepo baby

Henry Kaiser was not born into wealth. His father was a shoemaker at a time when the profession was transitioning from highly skilled hand-made production to semi-skilled factory work. Kaiser senior never made the transition. As a result, his son, Henry, was on his own to make his way in the world.

Kaiser started his career as a stockroom delivery boy for a dry goods store in Utica, New York. Then, he worked in the photography business, taking portraits and selling cameras and supplies both business-to-consumer and business-to-business. Eventually, he partnered with the store's owner and opened stores of his own along the East Coast. He did well in the photography business but was by no means a mover and shaker in the industry. He was a small business owner who was making a decent living.

That all changed when, having tired of the photography business and wanting to impress his future father-in-law with the hope of prospective wealth, he sold the business off and moved to Spokane, Washington. Kaiser went to work, first for McGowan Brothers Hardware, a hardware distributor operating at both the retail and wholesale levels, and then for a road paving contractor, the J. F. Hill Company.

Kaiser was in the right place at the right time. As the demand for automobiles and trucks grew, so too did the demand for asphalt-covered roads. Both the wholesale hardware and road paving businesses gave Kaiser the skills and insights needed to bid successfully on government contracts to build those roads. Getting and successfully fulfilling government contracts would become the mainstay of his expansion from small businessman to industrialist.

Industry does managed healthcare

By the end of the 1920s, Kaiser was a full-fledged industrialist, heading a company that built large-scale roads throughout the US and Cuba. In 1931, his company was part of a consortium called Six Companies, Inc. That company won the contract awarded by the Department of the Interior to build a dam on the Colorado River. The dam became known as the Hoover Dam. The dam was completed two years ahead of schedule and delivered under budget. Such a feat is practically unheard of today. At the time, it was one of the marvels of modern engineering.

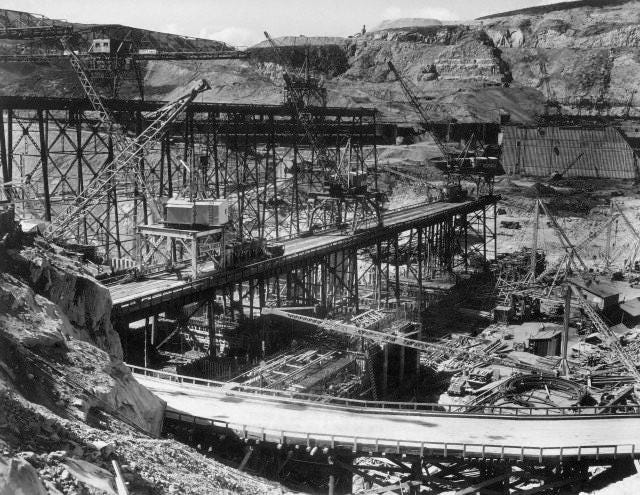

The Six Companies would then go on to win a government contract to build the Grand Coulee Dam on the Columbia River in Washington state. Construction started in 1933.

At the height of construction, ~8000 workers were employed to build the dam. In addition to paying a relatively good wage, averaging 80¢ an hour, the company provided housing for workers and their families along with three communal meals per day. Six Companies also offered something rare in industrial construction: a prepaid health plan for employees. That plan evolved into the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Plan (KPMCP).

Key features of the prepaid plan offered by the Six Companies included:

Comprehensive care for workers and their families, including spouses and dependents.

No extra out-of-pocket costs for health care visits.

Coverage for common illnesses and injuries.

Preventive care services, such as vaccinations.

Health education to help keep workers healthy.

Around-the-clock care through a team of doctors and nurses working collaboratively as a group practice.

Access to hospital services at a 35-bed hospital near the dam site.

Coverage for both work-related and non-work-related health care needs.

The plan operated on a prepayment system, where workers voluntarily paid a small weekly premium (initially $0.50 per week for a spouse and $0.25 per week for a child) to receive the services. (Given that the average wage at the dam was 80 cents an hour, the cost of coverage for a family was about 2 hours of labor per week.)

Kaiser expanded his operation into shipbuilding in 1939 as WWII loomed on the horizon. He perceived an imminent increase in demand for ocean-going cargo ships and intended to make some money by meeting the need. His company opened the first shipyard in Richmond, CA, that year. As with the Grand Coulee Dam project, access to the KPMCP health plan was offered to those employed in the shipyards and later, in 1943, at the steel mills the company opened in Fontana, CA, to provide material for ship construction.

In July of 1945, KPMCP opened enrollment to the public. At the time of his death, Kaiser’s KPMCP covered 1.6 million people. As of 2023, Kaiser-Permanente has 12.6 million members enrolled in the plan.

It’s interesting to note that although KPMCP gets a lot of attention for being at the forefront of health maintenance organizations, it was not the first to operate in the United States. La Société Française de Bienfaisance Mutuelle was the first prepaid health maintenance plan, established in San Francisco in 1849. Coal mining companies in the Lehigh Valley of Pennsylvania offered prepaid plans to employees starting around 1888. And, the Henry Ford Hospital, the starting point for the Henry Ford Health System, opened its doors in 1915.

The long and the short of it is that HMOs are nothing new. While the reasons for their existence might be more about getting injured workers back on the job as soon as possible rather than out of altruistic concerns, the outcome benefited both employer and employee: keeping the workforce healthy and active while keeping the cost of care low.

Sorta socializing medicine

Although it was started and run as a private entity, the Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Plan was indirectly funded by the US Government. The construction of the Grand Coulee Dam and the Liberty and Victory ships manufactured by Kaiser Corporation during WWII were government projects. Kaiser created and administered KPMCP, but government money made it all possible. In a way, KPMCP is an early example of government-sponsored healthcare that works.

The HMO as a model for Universal Health Care

Prepaid managed care plans offer many benefits. Consolidating services and equipment creates an economy of scale that makes operating the system cost-efficient. HMOs, such as present-day Kaiser Permanente, focus on promoting the long-term health of members rather than solely on healing the sick. Also, administration costs are lower.

HMOs such as Kaiser-Permanente are a good model for universal health care. They’ve been around for a while and have been proven to work. Administered properly, they provide healthcare at a cost lower than third-party insurance that supports a fee-for-service model. However, to make HMOs a feasible way to implement universal healthcare in the United States, two issues must be addressed.

First, measures must be implemented to prevent a single HMO from monopolizing healthcare services. Second, the government must address how to compensate HMOs fairly. As long as providers do not collude, several private, not-for-profit HMOs competing for membership will keep the cost of healthcare down and the quality of the services delivered up.

One way to address the issue of compensation is to have consumers pay directly for membership in the HMO of their choosing on a post-tax-deductible basis. The cost of membership is deducted from a member's tax bill. Also, membership subsidies can be offered on a need-based basis. Another way is for the government to pay the HMO directly by using funds collected through progressive taxation of the public. Other strategies will emerge as the matter is given serious thought. In any case, once these issues are addressed, given their past and current success, HMOs will be well-positioned to play an effective role in providing quality universal healthcare in the United States.

Kaiser’s legacy

Most of the businesses Henry Kaiser started have not survived. Kaiser Steel filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 1987. Kaiser Motors, which was started in 1945, became Kaiser-Jeep in 1963. Kaiser exited the automotive industry entirely in 1970, selling what remained for its interest to American Motors.

At one time, Kaiser's name recognition was equal to that of Rockefeller, Ford, FDR, and Eisenhower. Kaiser died in 1967 at the age of 85. For many, he was emblematic of what it meant to be a Captain of Industry. Yet, when reflecting upon his accomplishments, Kaiser said the following: “Of all the things I’ve done, I expect only to be remembered for my hospitals. They’re the things that are filling the people’s greatest need: good health.”

Hopefully, as the debate about universal healthcare continues, Kaiser's legacy will be remembered, and his approach to providing quality healthcare to all will be adopted. He proved it could be done at the industrial level. Why it still hasn’t been done for everyone in the United States is a mystery that should have been solved a long time ago.

I think it's really interesting that some of the earliest successes of HMO-style organizations were both examples of strongly-aligned incentives and interests:

1. Industry needs workers, and workers need to be healthy to produce value.

2. Immigrant enclave within a generally anti-immigrant population applying concepts of mutual benefit/aid. (Though still organized around industry and ability to work.)

Also, the idea of a health insurance premium being equivalent to a few hours of labor is inconceivable to my present-day mind.